I have wanted to write this text for an extended amount of time. Ever since I first saw the teasers that showed the conception of the two movies that concern us this time I have been possessed by some kind of infantile enchantment. It had some air of mythical. Headlines like “First shots of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie” or “First look of Cillian Murphy in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer” appearing in the usually bland feed of the Ennui Engine powerfully started carving themselves a place in my head. I have never given any importance to the eponymous toy neither to the figure of J. Robert Oppenheimer, PhD, before then – but both names carry connotations of heavy weight in the recent history. I somehow knew that both were things to witness when the movies released, so I calmly and comfortably started readying myself for their appearance in theaters.

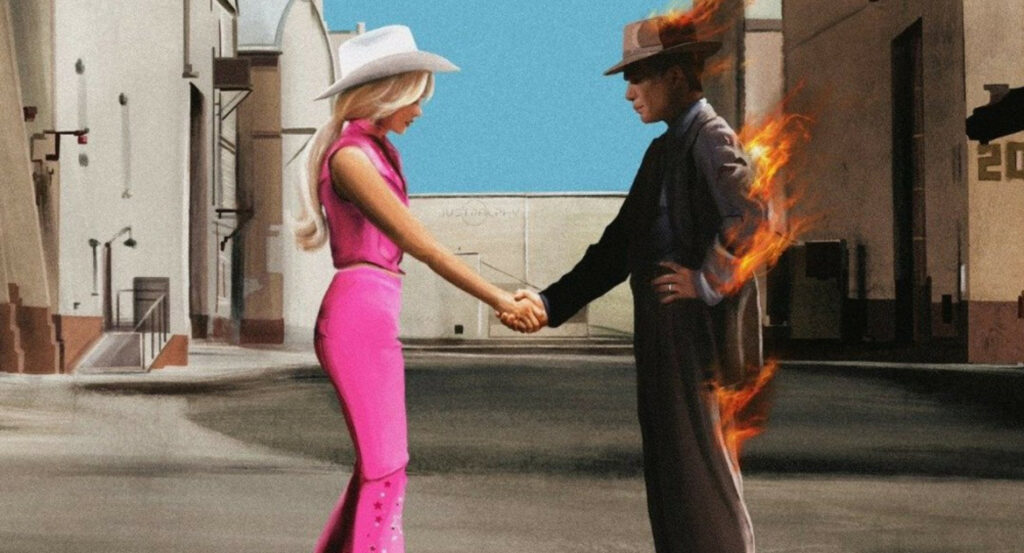

But I never imagined that the world would equally react to them. And not even less, tie both movies together, in a surprising yet increasingly amusing phenomenon. If I already had a hunch, the nascence of the Barbenheimer meme seemed to confirm it. In a quasi-mystic event, people around the globe noticed the same. Hell yeah.

Nevertheless, I did not even had the shadow of a doubt that I would enjoy them. We all know that expectation is a mischievous company, and balloons can explode when they are more-than-enoughly bloated – but I did not fear any kind of disappointment. I continued making myself comfortable with the thought that I was going to have a real blast with the newest concoctions of two authors of cinema that drive all the spectrum between casual watchers and intense connoiseurs crazy.

After the big day – pink shirt for Oppenheimer and black t-shirt for Barbie (yes, you read well) included -, I have been slowly rumiating thoughts and conclusions. I was so excited to share my experience with you guys, but at the same time fearful of not being able to convey anything the proper way. Both films are complex enough to have different lectures, but are also light and easy to digest. What if I fail at maintaining the standards of what the world has made of the Barbenheimer phenomenon? Writing Corners is usually very difficult to me, and this time I have all other circumstances are against me.

I am certainly amazed that this cosmic hunch we all got was definitely right – Barbie and Oppenheimer are a very match. Both in similitudes and oppositions. Leaving aside the initial easy counterpositions (female vs male, bright vs dark, happy vs somber, fantasy vs reality, comedy vs drama, etc.) that somehow fit in the puzzle that is Barbenheimer, we find stunning pairs.

Greta Gerwig and Christopher Nolan excel at something – they are filmmakers with their own authorship and peculiarities that make accessible movies. Both have their own universe of obsessions, topics, motifs, messages and imaginery; both are savvy in the world fo cinema; both transmit themselves in their works as any other auteur but… everybody find their films enjoyable. They have details for everybody, they make a multi-layered experience in which everybody will find something enjoyable and appealing to their vision. And furthermore, they have an unlikely skill that permits their layers to interact, so even their different audiences can perceive the details that, being their films under other hands, could escape them.

I remember having predicted that Barbie would be a serious (=with complexity and power) movie, and most of my interlocutors would look at me as in “WTF dude, it will be an absurd comedy 4 tha lulz”. And now, miraculously, everybody understands what I wanted to say. Greta Gerwig’s universe of questioning gender roles, societal customs, rules and issues peeks and unveils itself after Barbie has made enough fun of itself during the first minutes – and poses its audience very uncomfortable questions about what a woman is in our societies. Employing exemplar instances of farce, hyperbole, ridiculization and esperpento, and even place-switching applied on the female-male binomy, the film achieves a grand effect. Members of the audience belonging to either gender (or both, or neither) will have a blunt holistic view on what things are and how things are, and hopefully will be able to reflect.

Barbie is a flowing game of ever-switching contrasts that succeed themselves in a rapid spiral. We get burnt and frozen constantly, and the same way matter changes by the effect of elements, it intends to change our minds and establish a climate of uncomfort that (hopefully) will make us better. Returning to the beginning, the initial images of a cheerful, happy, absurd comedy are an amazing vehicle for planting the seeds of thought and revolution in the audience (if they accept them). Furthermore, Greta Gerwig has achieved it by collecting the fruits of previous powerhouses of cinema, modifying them the way she needs them to design her universe using comfortable tropes and images we all know.

If Barbie flaunts a meshing opposition of light and heavy, Oppenheimer does not stay behind it. What if I maintained that Nolan has not abandoned the action genre? In an unlikely way, a biopic of a scientist that could have all the odds of becoming a The boring world of Niels Bohr alike benefits itself of an accelerated, frenziful pacing and rhythm that gives the film an atomic-tier of thrill. The same way his counterpart Greta Gerwig does in her own way, Nolan employs his filmic dexterity in resources that suggest the pinnacles of grand, eloquent, strong to cathalize Oppenheimer to Hellenic levels. The American Prometheus, who gave humanity a boon and a curse at the same time.

Furthermore, exactly mimicking the anecdote of Barbie‘s potential audience statements, I had previously heard comments in the fashion of “what will be the interest of Oppenheimer? We already know the outcome of the story!” that could be answered in a parallel way. The story, the images, are just its envelope. One of the biggest innovations of Greek Tragedy was the intoduction of questions and shadows in already known stories – heroes, masters, manichaean exemplar figures of the past are put into question and scrutiny by the audience. The heroes are given the weight of their actions and have to deal with the (not always pretty) consecuences of them. The blank, guilty stare of Cillian Murphy’s quintessential interpretation of the eponymous scientist is enough a hint to understand this effect. We witness the struggle of Oppenheimer’s life and deeds, we are both approving and disgusted by his actions. He learns what he has done too late. He is a pawn in the grand scheme of things and has started something that has exploded in the wrong direction. It is up to us to interpret and judge Oppenheimer the same way he was judged in history, and in the picture.

Ever since the times of Erathostenes, scientific images become Homeric fire.

The two Barbenheimer films show a cover and an inside, a manifestation of the aforementioned interacting layers. They are as contradictory inside them as they are between each other, and they are as parallel and meshing as they are with their filmic counterpart. But this sympathetic contraposition does not finish here at all.

Greta Gerwig and Christopher Nolan have shown a tendency that has been well-attested in artistic production: the fixation with a figure. The countless examples of storytellers obsessed with a character that is at the same time a self-perceived reflection, projection and vehicle for their thoughts, that has marked the artist at some point of their life for never abandoning their backbone, are always present in the human history. Greta Gerwig-Barbie and Christopher Nolan-Oppenheimer are the latest examples of this psychologic phenomenon that can be previously seen, e.g, with Paul Auster-Stephen Crane or Darren Aronofsky-Noah (to name quick examples). The famous human contradiction, the union of the different, the identification with the repulsing, is omnipresent in this phenomenon: author-work, admirer-character, female-male, hero-antihero… they all coexist in the perceived game of contrasts that is Barbenheimer, and ultimately, the human being.

Coming to an end, I want to finish this Corner with my personal musings, my two cents after having satiated my hunger for filmic delight. I want to aunate this game of binomies in a single idea – my own personally-perceived theme, that may be only unique to me, but as valid as any individual conclusion of the Barbenheimer phenomenon. If I can say a prosaic theme that is equally present and monotonic in both films, and also a quintessential aspect of human life is, basically, that adulting is hard. We humans, regadless of our background -dolls or scientists, feminine heroines or modern Prometheii-, are constantly debating ourselves with countless contradictions, wanting to take control of our life but also bound to uncertainty and unexpected events that affect us. We all try, we all fail, we all might be right. We all have positive, altruistic, balanced aspects, and negative, egoistic, excessive traits that coexist. Life is all this game of coexisting opposites that attract and make us contradictory.

But we thrive and survive. Perhaps this is another reason why Barbenheimer triumphs. Because it humanity, condensed in a play of binomies. It always takes two playing together.